the new computational ontology

The work of Italian sociologist Vania Baldi, author of Otimizados e Desencontrados. Ética e Crítica na Era da Inconsciência Artificial [Optimised and Disconnected. Ethics and Criticism in the Era of Artificial Unconsciousness] draws on the philosophy and anthropology of technology. In this article, he challenges the unrestricted belief, blind optimism, and ethical negligence regarding the new systems of Artificial Intelligence.

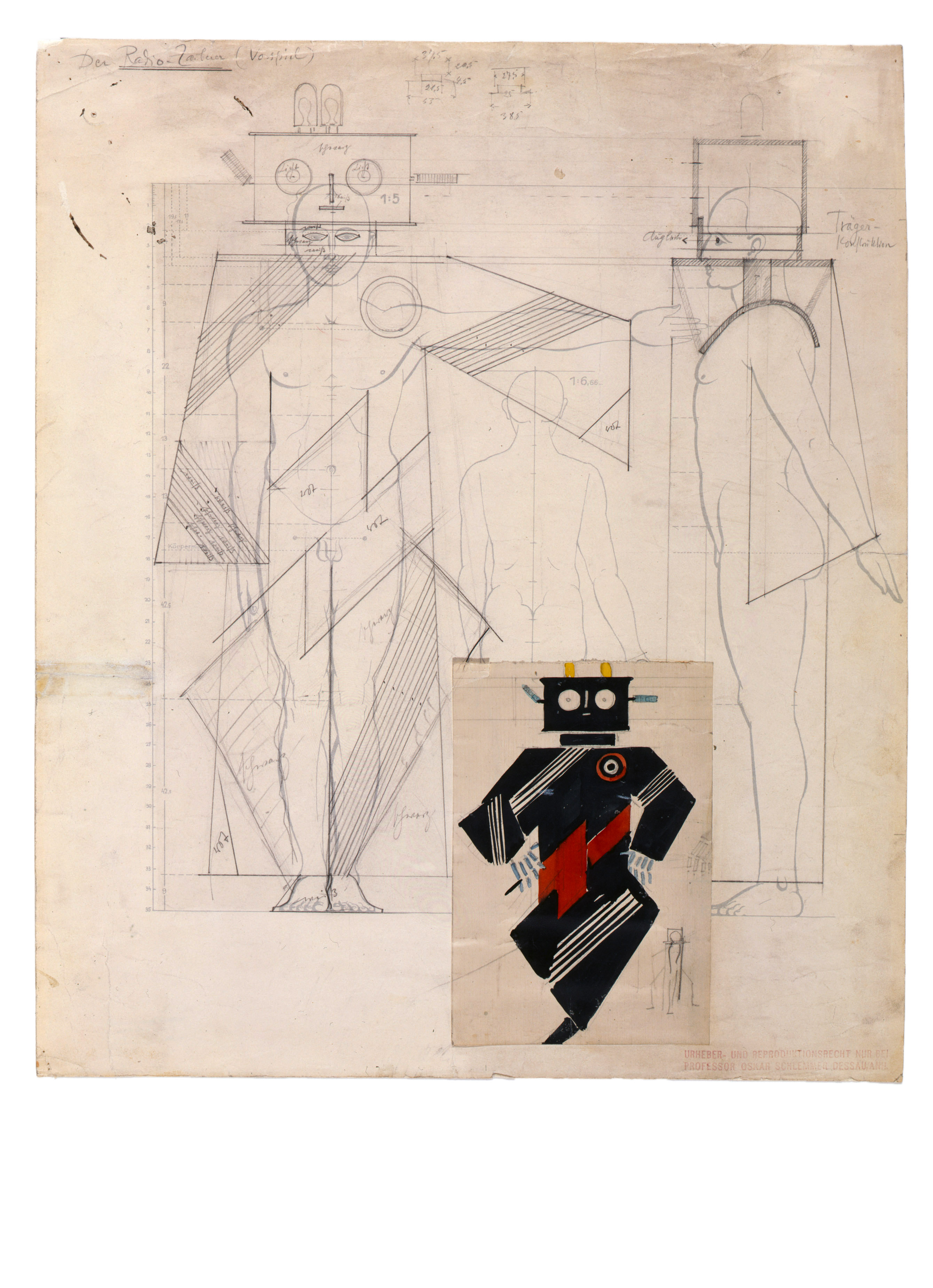

Oskar Schlemmer, Radio-Wizard, 1928 © Photo: Scala, Florence / bpk, Bildagentur für Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte, Berlin / Theater wissenschaftliche Sammlung der Universität zu Köln, Schloss Wahn, Cologne

What are the reasons for analysing and discussing the nature of the loudly trumpeted ‘generative intelligence’ of the new systems of Artificial Intelligence (AI)? Simply questioning the concept of ‘intelligence’ used in the realm of digital services and products, as well as the mediatisation associated with them, could seem like a linguistic caprice or conceptual purism. But when we add the adjective ‘generative’, the perplexity reaches a vaster scope, one where ethical and political concerns join theoretical ones.

The infosphere, which absorbs, records, calculates and categorises everything, represents our new computational ontology, a reality composed of AI systems that measure and process infinite data flows according to a logic of automatised learning designed by algorithms. Therefore, the reasons for questioning the type of intelligence at play here stem from our impression that what defines us as humans and social beings is now collectively viewed as obsolete and irrelevant. Have our abilities to act, think, assess, project and change (which is no less important) become outdated?

Before delving into these anthropologically existential questions, we should mention two recent studies that confirm the perplexity regarding the collective view in question. The first one reveals the extent to which the disbelief in political institutions and the belief in the virtues of technology is ingrained in common sense. It is a survey conducted by the Center for the Governance of Change at IE University, where a sample of 2769 citizens from eleven countries on different continents, was asked: ‘Would you rather have an algorithm making policy decisions or real legislators?’ According to the survey, in Europe the algorithm won with 51%, while in China, three out of four of the respondents chose the algorithm.

The second example refers to a review of the literature published in 2021 about the presence of ethical concerns in the field of computer sciences and coding: of the one hundred most cited articles published in the last fifteen years in the records of the two most important conferences of the sector (NeurIPS and ICML), only two mentioned and discussed the potential dangers of the AI applications presented. The remaining ninety-eight did not mention any dangers, thus eliminating the possibility of discussing them, although a significant part of the research deals with socially controversial fields of application, such as surveillance and disinformation.1

Two examples, among others, which show us the transversality of the critical naivety regarding the processes of technological innovation, and which suggest a view of AI that is reduced to the computational optimisation for which it was conceived. The debate promoted by technological companies seems to focus on the applicability of AI to everyday life, particularly its growing functionalities concerning productivity, without questioning what we, as a social and political community, want to do with it. Moreover, by associating intelligence with mechanisms for the multiplication of performance in task management, the media narratives devised by the leading AI investors reveal an instrumental view of human intelligence. The warnings about human substitution or extinction belong to the world of marketing and public relations, where advertisements and speculations about certain expectations aim to generate a ‘bubble’ whose value dispenses with any real materialisation.

What is at stake here is not the ‘promethean shame’ examined by Günther Anders in the aftermath of the Second World War, a shame that resulted from the feeling of insignificance that humans felt before their own technological creations. On the contrary, it is a feeling of blind optimism and childish euphoria (the ‘triumphal calamity’ mentioned by Adorno and Horkheimer in Dialectic of Enlightenment), which can create the worst scenarios (as we should have learned in the last twenty years with the ideology of the brave new world created by the digital market).

Maybe the pressing task to which we are called by the propagation and development of AI is the definition of the type of society that we intend to build in taking advantage of this computational re-ontologisation. If as a society we have a political project, we can try to make the most of AI’s influences on behalf of interests outside of finance, sociopathic entertainment, and competition as a gauge of social values. In conclusion, if it is decided that AI should be governed by a logic of social utility, then it is vital to understand the peculiarity of its intelligence and take advantage of the computational logic and architecture that underpin it. From this perspective, it is necessary to understand what we can really expect from it, since its automatised systems should not create illusions about its autonomy or be confused with self-management capabilities.

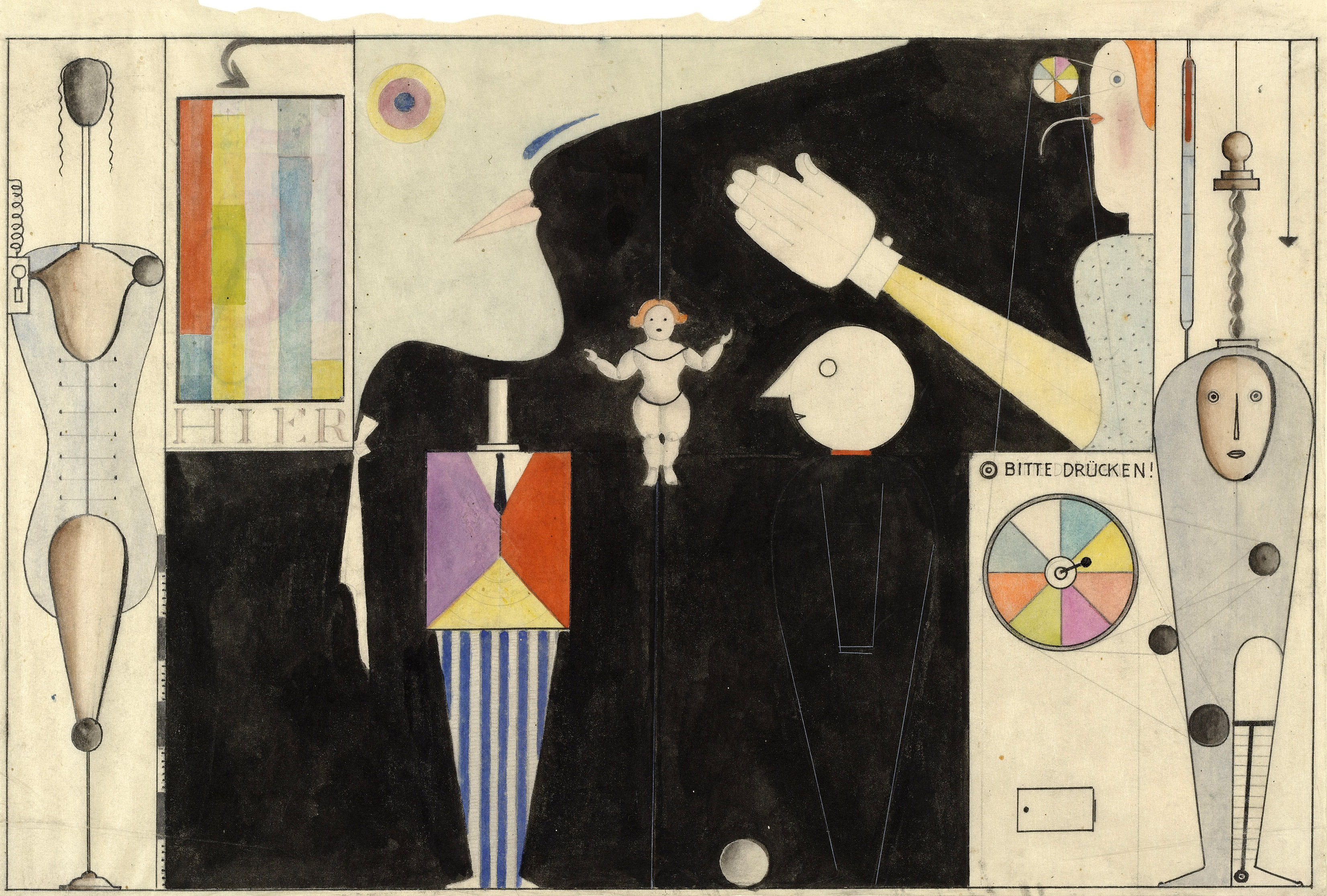

Oskar Schlemmer, Das figurale Kabinett [The Figural Cabinet], 1922 © Photo: Scala, Florence / The Museum of Modern Art, New York

acting as interfaces among other interfaces

How does AI work? What are its operational characteristics? Does its way of acting reflect some cognitive plasticity? Do its procedures imply doubt and adaptability to contexts? Can action and intelligence be separated?

There are different types of actions: some demand a motivation, an intention, a stimulus from the social environment that allows for the maturation of a psychological orientation, an ability to face unexpected contingencies; another type of action is machine-like, executing and obeying an input/output logic. AI systems apply the second logic of doing/acting in a technologically predetermined way, without the intellective ability that allows for an assessment of what is at stake, a suspension of judgment, a flexibility in the face of unforeseen events or a retrospective reflection.

From a psychological and sociological perspective, action implies an intentionality based on historical consciousness and self‑awareness, requiring requests for clarification, the weighing of the values at stake, and the time to reconcile one’s feelings with what is socially seen as convenient. In short, justifiable reasons for acting the way we have chosen, or for changing our minds and retreating. In this sense, an intentional action is also linked to responsibility, to an ethical reflection that relates to cultural contexts invested with histories, relationships, passions and implicit values. On the other hand, AI systems make choices in an automatised fashion, through a not very intelligible computational logic, raising questions of a moral nature about the reasons behind its actions.

[...]

Share article